November 11, 2025

When a location experiences both extreme wind and extreme rainfall around the same time, the likelihood of fallen trees, power outages, and damage to houses and infrastructure increases. New research from the NESP Climate Systems Hub is working to understand when and how these wet/windy extreme events occur, to help people better prepare for them in the future.

Understanding severe weather events helps to improve risk assessments, adaptation plans, building codes, and emergency planning. The NESP Climate Systems Hub has advanced this research through multiple projects and continues to collaborate with decision-makers in the energy and emergency services sectors to match weather data with their data and insights from real, on-the-ground impacts from past events of this nature.

Where and why do wet/windy events happen?

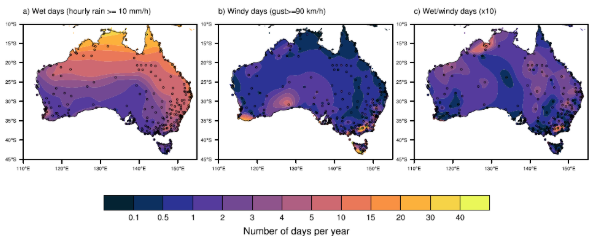

This study used weather station data to understand how the frequency of heavy rainfall, strong winds, and their combination, vary across Australia. We defined ‘strong winds’ to be when a day recorded at least one damaging wind gust of at least 90km/h, while extreme rain was based on rainfall totals of at least 10 mm in an hour.

While the strongest winds in Australia are recorded in the tropical cyclone prone regions around the northern coastline, damaging wind gusts above 90km/h are most common in southern Australia, particularly close to the coast and at high elevations. In contrast, heavy rainfall is most common in the north and east. Our research showed that wet/windy conditions where both thresholds are exceeded on the same day in the same location can occur anywhere in country, and are most common in northern Australia.

What does this figure show? Left map (a): How often places get very heavy rain (≥10 mm in an hour) each year. It’s most common in the north and coastal areas, rare in the south and inland. Middle map (b): How often places get very strong winds (gusts ≥90 km/h) each year. These happen more in southern coastal areas and high elevations, less in the tropics. Right map (c): How often heavy rain and strong winds happen on the same day each decade. This is rare everywhere, usually only a few times per decade, but hotspots include northwest (cyclones) and mountain regions. Dots show the locations of the weather stations used to produce this map.

We found that wet/windy extremes in northern and central Australia are generally related to tropical cyclones or thunderstorms and primarily occur between October and March. In southern and eastern Australia wet/windy events can occur throughout the year but particularly in the summer and often occur when thunderstorms develop within a low-pressure system or cold front.

Past studies on wet/windy extremes have used global reanalysis datasets, which are a gridded model of the world’s weather on a given date, typically at a 25km resolution or coarser. Interestingly, our study showed that these datasets failed to capture wet/windy extremes from thunderstorms, leading to an underestimation of wet/windy events in northern Australia. These datasets also tended to underestimate the frequency of wet/windy extremes in the summer months, particularly in southern Australia.

To get the details of small-scale features like thunderstorms we need high-resolution datasets such as the new Australian BARRA-C2 reanalysis. This better represents the patterns we see in observations, and provides an improved mapping of how the likelihood of wet/windy extremes varies across Australia. This research highlights the importance of using high-resolution datasets for accurately understanding the current and future risk of these impactful extremes in Australia. This research highlights the importance of using high-resolution datasets for accurately understanding the current and future risk of these impactful extremes in Australia.

What’s next?

This study chose a single threshold to define extreme rain and wind, but are these actually the conditions where extreme rainfall and wind cause the most damage? And do the most relevant thresholds for where damage occurs vary across the country?

A current NESP project is further improving our methods to ensure we capture and analyse the most important and damaging wet/windy events. Improving our methods and datasets will help us better understand where and how these events occur and how they may be changing in a warming world, particularly as rainfall extremes intensify.